Southeast Asia VC Drought Survivors

Source: AVCJ.comAs weaker sentiment for technology risk cools venture capital markets globally, Southeast Asia is lagging in limbo. Investors remain bullish but continue to hold their fire amidst questions around valuations

The initial shock of COVID-19 provided much of Southeast Asia’s start-up scene with its first wake-up call around undisciplined investment, over-aggressive business expansions, and playing loose with unit economics. That made the belt-tightening required in the industry’s current pullback more palatable, but there is still a sense that things are different this time.

Most importantly, the chill on the market in the past several months has not been a shock but

part of a predicted long-term cycle. This means that while a flight to quality and runway preservation have returned as dominant themes, they have been joined by heretofore less urgent calls for more immediate profitability.

For Southeast Asian venture, as an emerging asset class, the biggest question is to what extent a global slowdown in risk-taking and receding valuations will meaningfully stunt ecosystem growth.

The idea that hot money is leaving the market is most often exemplified by the retreat of so-called crossover investors such as SoftBank Vision Fund and Tiger Global Management. But regional actors are roundly expected to plug the most essential holes in this gap, at least until the global players return.

Appetite among institutional investors for Southeast Asian funds is another story, particularly given rising anxieties around portfolio valuations. Down rounds have not yet surfaced in the region en masse, but this is widely considered inevitable in the near term.

The latest indicator of the indirect global stress on Southeast Asia is the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) earlier this month. Start-ups in the region are largely unexposed – especially versus those in India, China, and North Asia – but some collateral damage is expected in terms of general liquidity. Many US investors are at a standstill, and M&A from the US into Southeast Asia appears set to slow even further.

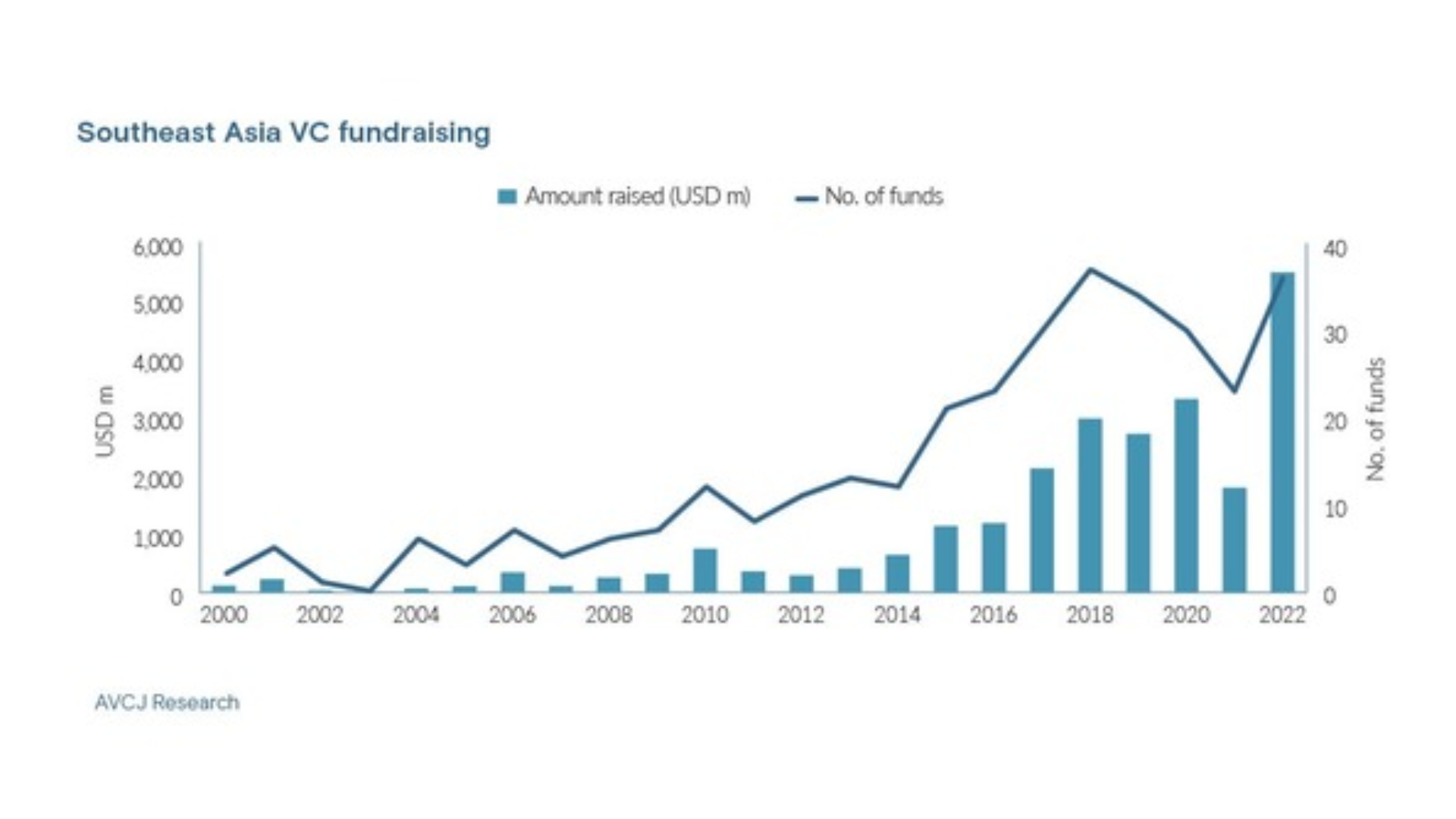

Nevertheless, VC fundraising targeting the region reached a record USD 5.5bn in 2022 with standout hauls from the likes of Sequoia Capital (USD 850m), Jungle Ventures (USD 600m), and Lightspeed Venture Partners (USD 500m). The latter two will also target India. In the past few months, Asia Partners and Openspace Ventures have launched ASEAN funds targeting USD 600m and USD 650m, respectively.

“For a long time, Southeast Asia has been flush with capital and had the luxury of being more growth-focused than unit economics-focused. So, this is a time of reckoning for everyone in the ecosystem, from founders to VCs to consumers,” said Pinn Lawjindakul, a Singapore-based partner at Lightspeed. “Now, for the first time, they have to think about what value they want to pay for something.”

Reality bites

Justification for ongoing confidence is often as simple as pointing to Southeast Asia’s social mobility and modernisation fundamentals, along with the long horizons of VC. Even the most visible cracks in this story, the tech ecosystem’s first widespread layoffs, are often dismissed as a proactive function of cash burn control and scant compared to the number of jobs created by the digital economy in recent years.

Lawjindakul, for example, estimates that only about 20% of Lightspeed’s Southeast Asia portfolio companies have been compelled to rationalise their workforces in the current slowdown. None of the firm’s investees in the region has exposure to SVB.

Like many investors, however, Lightspeed has slowed its pace of deployment to a pre-boom norm. The firm’s number of transactions per year jumped from 1-2 to 4-6 during the pandemic. Between the first and second half of 2022, deal flow fell 20%-25%, while formalised investments declined 40%-50%.

This is partially explained by the idea that start-ups don’t want to face a tough valuation environment and potential down-rounds. Even if a marginal increase in valuation can be achieved, going to market in a climate of uncertainty can be viewed as a sign of desperation.

At the earliest stages, there is also a sense that many tech professionals are simply not taking the leap with their own businesses. The thinking is that economic uncertainty has taken the shine off entrepreneurial risk-taking and kept the best and brightest under more established employers.

In anecdotal terms, up to half of the deals happening in recent months have been for stable category leaders, which have seen valuations hold up on the back of steady investor interest.

A smaller but significant minority of deals are represented by bridge rounds at flat valuations.

Distress-oriented extension rounds are considered prospective but not yet pervasive.

The bulk of bridge rounds in Southeast Asia have tended to be 20%-40% the size of the company’s prior round and completely internal, according to Brian Ng, a VC-focused partner at Singapore based law firm Rajah & Tann. Openings for new investors have come to light in the form of secondaries, where recently active angel investors feeling pain in pubic markets will seek liquidity in their private holdings.GPs’ annual portfolio valuations for 2022 have yet to come to light, but they are expected to reflect relatively minor adjustments. This will be explained in part by the idea that tech on public markets is heavily associated with big tech infrastructure rather than the resilient software-as-a-service (SaaS) models preferred by VC firms.

Still, SaaS valuations appear to be roller-coasting with everything else. Pre-pandemic, SaaS start-ups in Southeast Asia traded at around 10x-12x their annual subscription revenue, according to two industry participants. That figure dropped to 8x in the panic of early 2020 before scaling as high as 30x in 2021 and 2022. It’s now back to around 10x-12x.

Other segments that ran hot in the past two years may have experienced even wilder rides, including cybersecurity, e-commerce, and concepts related to work-from-home and remote consumption.

“If you are in an earlier vintage, 2010 to 2015, you have a problem because all those guys have to exit this year. Even a secondary exit at the fund level is going to be massively affected because your fund-level MOIC [multiple on invested capital] will drop drastically,” said Vicknesh Pillay, a founding partner at Singapore VC firm TNB Aura.

“Though revenues have increased from the time you invested, the public comps have decreased, so you need to revalue your entire portfolio. The marks will be reduced, but more importantly, there’s pressure to create DPI [distributions to paid-in], which I don’t think is going to happen in 12-18 months.”

Picking winners

The damage implied by this scenario is contained by the hockey stick-shaped history of the ecosystem’s development; annual VC fundraising targeting Southeast Asia didn’t cross the USD 1bn mark until 2015. The average fund size during the 2010-2015 period was only USD 46.5m, according to AVCJ Research. Last year, it was USD 152.3m.

TNB Aura is an advocate of managing this risk with compact portfolios that allow for private equity-style stewardship of companies. Since July last year, the firm has required all 20 of its investees to have 30 months of runway. Every company needs a plan to be profitable by 2024.

TNB Aura also insists on having a board seat for every company it invests. This strategy resulted in the entire portfolio emerging from COVID-19 unscathed. About 10% of the portfolio has had to raise an extension round since industrywide investment dropped off mid-2022.

Investors with larger portfolios and less control tend to expound the virtues of diversification and upfront discipline in due diligence. 500 Global, which has backed more than 340 companies in Southeast Asia, doubled down on the region last month with the recruitment of three new partners in Singapore, Malaysia, and the Philippines.

Vishal Harnal, a Singapore-based global managing partner at 500, said that even in a recession in a developing region, there are still winners in technology. He identified distribution, logistics, supply chain, healthcare, and education as areas likely to increase in adoption in a downturn. Approaching them in this context is merely a matter of adjusting the playbook.

“It takes some sort of real shock to the system, or some kind of cataclysmic event, for us to change our minds about entering a market,” Harnal said. “Is now the time to start a Ukraine tech fund. Probably not. It takes that kind of event to shake our view on a market because we base decisions on what it will look like in the next 5-10 years.”

This is not to say there isn’t a geography lens to debates around the current macroeconomic pressures on Southeast Asian venture capital.

Indonesia, for example, is the outlier in terms of inflated, un-updated valuations, according to three sources familiar with the market. They claim that down-rounds in the wake of an overexuberant 2020-2022 are proliferating in the country in hushed circumstances. One nonsoftware company, incubated by Y Combinator, was said to fetch a valuation of 100x annual revenue before recently closing down.

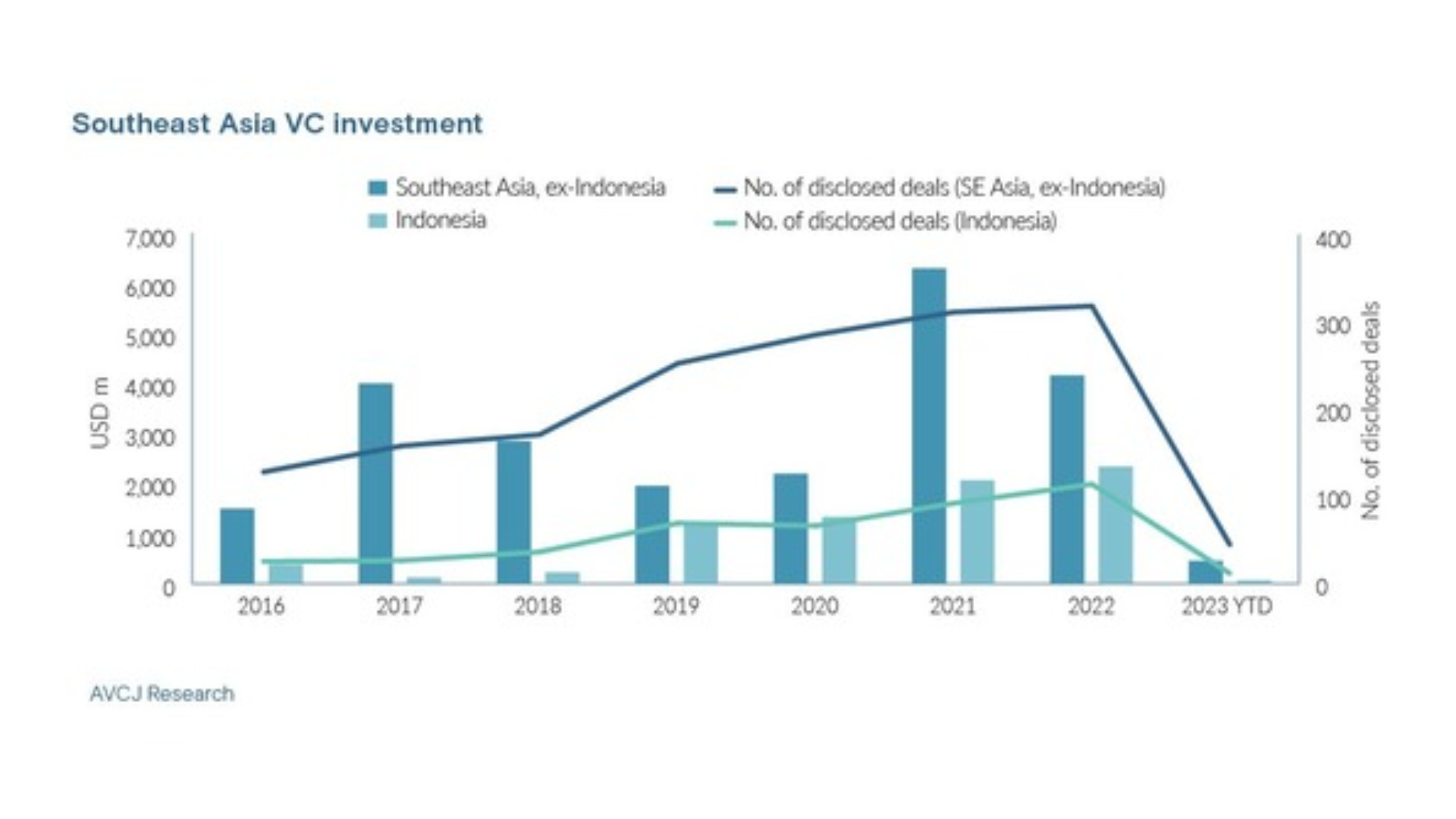

Across Southeast Asia ex-Indonesia, the average VC deal size during the boom period of 2021-2022 was USD 14m, a 77.2% increase on the average for the five prior years, according to AVCJ Research. In Indonesia, the average deal size in 2021-2022 was USD 16.3m, a 143.3% increase on the five prior years. The discrepancy will be felt in capital raising rounds first but most painfully in exits.

“Investors that invested at 15x-20x are likely to think any offer to buy their company is a lowball offer, even if it’s the right price. I think the real wreckage in Southeast Asia, particularly in Indonesia, is yet to come because the top of the market wasn’t that long ago,” said Field Pickering, head of VC at Singapore’s Vulpes Investment Management.

“Companies that raised at the very top are only now going back to the market, so the next 6-9 months is when we’ll see the real pileup of overvalued companies.”

Desirable debt

Vulpes, a multi-strategy alternatives investor, traces its history back to the early 2000s when it was one of the largest hedge funds in Southeast Asia and an early experimenter in venture capital regionally. It is not active in venture debt, but in the current environment, it considers the idea of getting paid cash regularly to take equity risk increasingly attractive.

Paul Ong, a partner at venture debt provider InnoVen Capital’s Southeast Asia practice, describes a fledgling asset class in the region as bolstered by broader VC woes. It’s worth noting that InnoVen was formed from SVB’s Asia business before being acquired by Temasek Holdings in 2015.

“I think there’s an element of that in pretty much every deal that comes to us now,” Ong said, referring to start-ups looking to venture debt as a way of raising capital without facing the spectre of a down-round or flat-round.

He echoes the notion that with reduced valuations, regional M&A and consolidation activity is heating up; TNB Aura’s Pillay said several of his portfolio companies had been approached by smaller counterparts hoping to be absorbed. Some of these proposals were said to be in “deep” discussions. Venture debt is facilitating such discussions.

“We’ve spoken to a lot of growth-stage businesses that raised large rounds last year and have very healthy cash balances but are still excited to explore borrowing because they see opportunity to grow inorganically,” Ong added. “They want to be able to press ahead with these opportunities without eating into their balance sheet.”

There’s reason to believe this trend – if it materialises – would be weighted toward later development stages. At the earlier stages, valuations have proven more stable and regional funding sources more plentiful.

Although seed-stage transaction sizes spiked as high as USD 100m during the pandemic in more established ecosystems such as the US, they have stayed in a range of USD 6m to USD 15m in Southeast Asia. The same cannot be said for more mature start-ups – which sets up a potentially delicate growth-stage market in the near term.

“You might see aggressive investment around the Series B stage this year, providing liquidity at a very steep discount to the best companies that unfortunately got their valuations wrong 18 months ago,” Pickering said.

“But the risk is you get a bad name in the market, even if you argue that you’re providing a service to these companies. You have to structure it so you’re not just wiping out early investors.”

The key to successful down-rounds in terms of deal mechanics is in balancing the anti-dilution clauses for existing shareholders with sweeteners for incoming investors such as preferred liquidation and redemption rights.

In most cases in Southeast Asia, the solution is likely to be a complete reset of the cap table, whereby all parties get the same valuation with ordinary shares and liquidation rights. The incoming investor sets the bar in terms of valuation, and existing backers will benefit from going into the negotiation with more units.

Green shoots?

But this is largely theoretical. Ng of Rajah & Tann hasn’t tracked any such activity since questions about valuations began intensifying last year. However, he does see pressure in the early growth stage.

In one anecdote, he describes a regionally active start-up with a valuation of around USD 200m that couldn’t close a funding round quickly enough, ran out of runway, and was submitted to a rescue restructuring. The viable parts of the business were moved into a new entity, and the existing VC investors were reorganised around it.

“Companies around that valuation – USD 200m – that were slightly aggressive before in terms of valuation are finding it difficult to meet the cash runway and just going under,” Ng said, adding that he sees green shoots in the deal market that suggest the funding winter is almost over.

“This is obviously one of the more drastic situations because the whole company had to be restructured. Closing some offices, that’s something that happens on a regular basis.” Cautious optimism appears to be the prevailing viewpoint across industry participants, but the degree of caution varies.

Southeast Asia is accustomed to commodity cycles, currency fluctuations, and all manner of political upheavals, most of which represent relatively short and sharp disruptions to an implacable overall growth story. COVID-19 proved yet another challenge in this vein. The current tech rout, by contrast, is likely to be the first long-term region-wide economic event in the ASEAN start-up era.

In this environment, the company-level cost-cutting that characterised the early pandemic will persist, and it will give way to more risk-taking as valuations normalise. But that narrative will not unfold without significant weeding. Ultimately, the shakeout is understood to be a positive development for the maturation of the ecosystem – at least from the perspective of those who don’t get shaken out.

“This year is most likely going to be painful in terms of valuations coming down and portfolio valuations adjusting down. We’ll see slower deal activity, and I don’t think it’s going to pick up dramatically in the second half. I think it’s going to take us into next year, so strap in tight and focus on your portfolio companies until then,” said Ben Balzer, a Singapore-based partner at Bain & Company.

“But long term, this is not an industry that has overheated so much that we’re looking at a cliff or any major correction. This is a natural cycle we’re going through. If your portfolio is diversified, you can withstand this and you should be well positioned for the next few years.”